George Mills was born August 30, 1844 near Mills Springs in Polk County, NC. His mother was Mariah Mills, a slave belonging Ambrose Mills who owned a plantation on Green River. George Mills was sold to a Hendersonville lawyer named William Bryson when he was 13 years old. He became the valet of Bryson’s son Walter M. “Watt” Bryson. Watt Bryson was 22 and a medical student at the time. George Mills and Watt Bryson hunted, fished and roamed the fields and forests together and became good friends. Bryson was young enough that he and the young slave could relate to one another and he gave his young valet a lot of attention. If you are good to a child in the 10 to 15-year-old age bracket, you will usually have a friend for life — they don’t forget it. The reverse is also true. If you are mean to a child in this age group, they will detest you the rest of their life.

Watt Bryson had just returned from Charleston with his medical diploma when the Civil War broke out. Company G was soon formed in Henderson County. Walter M. “Watt” Bryson enlisted in Company G on May 15, 1861. The men of Company G elected Watt Bryson as their Captain. Company G became part of the 35th Regiment, NC Troops of the Confederate Army on November 7, 1861. They were sent to Camp Mangum near Raleigh to train. When word reached Hendersonville that Watt Bryson had been commissioned as a Captain, his father William Bryson sent George Mills to Camp Mangum to take care of Mr. Watt. Bryson told Mills, “Look out good for that son of mine and be sure to bring him home when the war is over.”

George Mills went with Watt Bryson as he fought in several battles including Seven Pines and Malvern Hills. Bryson’s unit became part of General Lee’s Army. He was with Lee when the Confederates captured Harper’s Ferry in September 1862. The night before the Battle of Sharpsburg (as the South called it, the north called it Antietam), Bryson called Mills to his side. He gave George Mills his gold watch and $400 dollars to keep for him. He told Mills, “Give the money and watch to my dear mother should I not survive tomorrow’s battle.”

On September 17, 1862 over 24,000 soldiers of the north and south died at Sharpsburg. Horace Greeley called it the bloodiest day in American History. Watt Bryson was one of the men that died in the battle. He was shot in the temple with the bullet exiting the other temple. George Mills searched everywhere for Bryson after the battle. Some friends of Bryson recognized Mills and told him where Bryson’s body was. The body was put in an empty cabin outside of Sharpsburg. Mills sat up all night with Bryson’s body (a mountain custom up until the 1960’s). He was determined that Bryson’s body would not be thrown into a ditch with the rest of the Battle of Sharpsburg’s dead. He remembered William Bryson had told him to bring his son home.

George Mills youngest daughter Mabel Mills (1892-1963), said that somehow in the confusion of the battle, Mills put Bryson’s body on a train to Fredricksburg, VA. He took $100 dollars of the $400 Bryson had given him and bought a heavy iron casket for the body. Bryson’s casket was bolted together and sealed with cement. The nearest train station to Hendersonville was at Greeneville, TN. With the war ragging all over Virginia it took a long time for Mills to get the body to Greeneville, TN, even by train. He hired a wagon and driver to haul him and the body to Hendersonville. When a stage came along he told the driver to leave word at Hendersonville to tell William Bryson, he was bringing his boy home. Mills knew the stage could travel much faster than the heavy loaded wagon and he wanted Watt Bryson’s parents to know he was coming. It took Mills three days to reach Hendersonville. He spent the first night at Paint Rock in Madison County and the second night on the west side of Asheville. Late in the afternoon on the third day George Mills reached the Bryson home in Hendersonville. The next day George Mills helped dig the grave for Walter “Watt” Bryson at the Methodist Church at the corner of Sixth Avenue West and Church Street in Hendersonville.

George Mills joined the Henderson County Home Guard soon after his return to Hendersonville. Mills joined the Watt Bryson branch of the Confederate Veterans Association. He attended most of their meetings and served as a delegate to the National Confederate Convention. Mills daughter Mabel Mills went with her father to three national conventions after he was too old to go by himself. She said she attended the conventions in New Orleans, Memphis and Richmond with her father. Mills received a Confederate pension from North Carolina in his later years. In the days before Social Security this was about the only pension there was. It may not have paid as well as a Union pension but it was a big help. On September 5, 1913, at a meeting at the Henderson County Court House, the Daughters of the Confederacy voted to award George Mills the Cross of Honor for his service to the Confederacy.

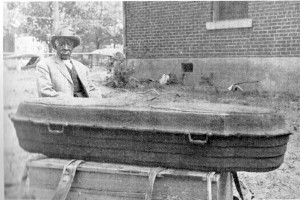

In early 1923 the Methodist Church outgrew it’s building. They decided to move the graves in the church cemetery to Oakdale Cemetery. Walter “Watt” Bryson was one of the graves moved. George Mills, then 80 years old, stood by as they dug up Bryson’s grave. He brought a picture taken while sitting next to the iron coffin he bought for Bryson 61 years before. The coffin was still in good condition. Mills went with the coffin to Oakdale Cemetery and watched it reburied at Oakdale Cemetery. George Mills died three years later on June 3, 1926 at the age of 82. Mills was buried in Oakdale Cemetery not far from Watt Bryson’s grave and has a Confederate tombstone on his grave.