The amount of traffic on the old drover’s road peaked in the 1830s and 1840s. During this period of time some 150,000 hogs would pass through Asheville in both the months of November and December. Stands lined the French Broad River at intervals of eight miles. Eight miles was the normal speed for all the different types of livestock to be moved in one day. If they moved any faster their animals would lose too much weight which would reduce their selling price. The faster they moved, the more animals that would successfully escape into the woods. The people that lived along the drover’s road would often find hogs, turkeys, ducks and other livestock in the woods near the road that had escaped from their owner. Since it would be almost impossible to tell which one of the 100s of drovers they belonged to, locals would just take the animals home with them. This pretty much eliminated the need for a livestock market in Asheville. You wouldn’t have much luck bringing hogs to Asheville to sell when the residents were getting them for free.

The people who owned stands along the drover’s road made a good living. John Garrett’s stand was located one mile below Hot Springs. John E. Patton owned a stand across the river on the other side of Hot Springs. It was called White House. At the mouth of Laurel Creek was a stand run by David Farnsworth. Zach Candler’s stand was at Sandy Bottoms. The next stand belonged to Hezekiah Barnard. Barnard said he had 110,000 hogs stop at his Inn in one month. Samuel Chunn’s stand was at Pine Creek. Joseph Rice’s stand was below Marshall. David Vance’s stand was located on the other side of Marshall. He once had 90,000 hogs stop at his stand in one month.

Many stands were well known for particular or specialty items. Widow Frisbee’s stand was famous for its sauerkraut. Widow Patton was famous for her apple brandy. The stand at Fletcher was run by a doctor. He not only served the Fletcher/Hooper’s Creek area as a physician but also doctored the ailments of the drovers. Wash Farnsworth’s stand was believed to be the only one operated by a black man. Wash built a series of cabins at his home for drovers to spend the night.

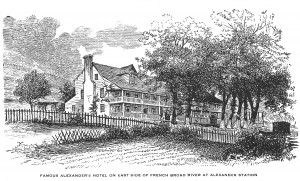

Alexander’s Inn located just north of Asheville at the town of Alexander was the finest Inn on the drover’s road. It was known from Charleston to Cincinnati as a plush (for its time) summer resort. In the fall after the end of the summer season, it became a stand for the drovers. Alexander’s Inn was run by James Mitchell and Nancy Foster Alexander.

The drovers were usually the farmers who owned and raised the livestock. Few people were professional drovers who bought a farmer’s animals and took them to market in hopes of making a profit. This was too risky for most people. The price of hogs and other livestock would greatly fluctuate according to the price of cotton. Hogs generally brought half the price per pound of cotton. Drovers were usually paid ten to twelve dollars plus room and board for making the trip to South Carolina and Georgia.

Hogs were the major livestock to travel the old drovers road but far from the only livestock to be seen. Four or five hundred ducks would be driven down the road at one time. Turkeys were often driven down the road. Four to six hundred turkeys (lead by a “master” gobbler) would strut down the road in a line that would stretch for 400 yards. They would stop at a stand at night, be fed corn and then roost in the trees at night. They were noted for being very hard to get down from trees in the morning to resume their journey.

Huge amounts food were needed by each stand. It took eight bushels of corn to feed 100 hogs. It also took on average one drover for each 100 hogs.

The typical meals served to the drovers consisted of boiled cabbage, platters of spare ribs, sausage, pots of dried beans, baked sweet potatoes, plates of biscuits, corn bread, and cracklin’ bread. The drinks were buttermilk, sweet milk and coffee. The cost of a meal was 25 cents. Most stands also sold whiskey but that was extra.

The stands needed 1000s of bushels of corn to feed the drover’s livestock each year. Area farmers grew hundreds of acres of corn to feed the animals. Stands would make deals with area farmers for so much corn a year. They would then send out word to each of the corn suppliers to bring a certain amount of corn on a particular day. In the fall wagons were often lined up for over a mile delivering corn to the stands. Farmer’s were paid 50 cents a bushel for their corn. Stands in turn sold them to the drover’s for 75 cents a bushel. Drover’s often bought their feed on credit. They would then pay the stand owner on the way back home after they sold their livestock.

Everyone knew the drovers would be carrying large sums of money back with them when they returned from South Carolina and Georgia. The drovers had to be careful as robbers occasionally tried to rob them on their trip back home. There was a black man who would often stop returning drovers and steal their money. He had killed several drovers over the years. One night he jumped from the side of the road and grabbed a drover’s horse and stopped it. He was a little to slow this time. The drover shot and killed the man. He placed the robber’s body on the back of his horse and went on to the next stand. When he arrived, he called out to the owner of the stand that he had killed the black man who had robbed and killed so many returning drovers. Everyone at the stand ran out to see the killer. The owner of the stand brought a lantern. When he held the lantern close to the body, a woman who worked there screamed. The dead man was her husband. He had put black shoe polish on his face to fool people into thinking it was a black man that had been robbing and killing drovers.

The number of drovers began to drop off by the end of the 1850s. The railroads began to slowly spread over the country. The Civil War put an end to the need for livestock to be brought to South Carolina and Georgia. Everyone was fighting in the war. Little cotton was being grown or sold. People had no money to buy anything. Kentucky and East Tennessee began to sell their livestock to the north. You did not have to drive livestock very far to reach a railroad. After the Civil War people in South Carolina and Georgia had little money to buy anything; therefore the drovers only returned in small numbers. The railroads expanded rapidly after the war and the drovers almost disappeared by the 1870s. Someone might drive five or six hogs or four or five head of cattle to Asheville or Hendersonville to sell. That was by no means a drove. In the 1830s and 1840s a real drover might lose that many animals a day that would slip off in to the woods. The drovers disappeared as fast as they appeared in the early 1800s. The stands disappeared almost over night. They reverted to common farmhouses, though big ones, or were torn down for the lumber or left to rot.

Local historian Bruce Whitaker documents genealogy in the Fairview area. If you have photographs, documents or history on residents of the community, call Mr. Whitaker at 628-1089 or send an email to him at [email protected].