North Carolina was likely the poorest state in the south. It had no great rivers that ships could navigate. The state had a few minor port cities, but none of those had a good harbor. Compared to all the other southern states it had the worst transportation system of any state. Before the railroad everything had to go by wagon or ox cart in North Carolina. Ships were by far the cheapest and fastest form of transportation. Almost anything you wished to buy was 50 to 70 percent cheaper in Richmond, Portsmouth, Charleston, Savannah and Augusta. North Carolina, located between wealthy South Carolina and Virginia, was often described as a “valley of humility between two mountains of conceit”.

Buncombe, Henderson and Madison County had one thing going for them; the shortest and most travelable route between North Eastern Tennessee and Kentucky to South Carolina and Georgia passed through their counties. Livestock drives were small in the early days. When Bishop Francis Asbury first visited area, he stopped at Captain Thomas Foster’s home in what is now called Biltmore. He preached at Foster’s house and spent the night. The next day, Sunday, he went to Asheville to preach. On Monday, November 10, 1800 Asbury wrote in his journal, that he left Asheville and went back to Thomas Foster’s on the Swannanoa River. He saw a drover with 33 horses. Northeast Tennessee and southeast and central Kentucky began to grow rapidly. They needed a market for their large herds of hogs, mules, turkeys, ducks, horses and other livestock. The rivers were the cheapest way to market for most goods but not animals in Kentucky and Tennessee. The big markets for livestock were South Carolina and Georgia. If you shipped hogs or mules by boat it would take months to go down the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers to the Mississippi River. Then, you had to go down the Mississippi from Cairo, Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico at the tip of Louisiana. From there you would sail around the tip of Florida all the way up the coast to Savannah and Charleston. Just the feed for the animals would take up most of the room on a ship. The only cost effective way to get livestock to South Carolina and Georgia was to drive them the 200 to 300 miles over land.

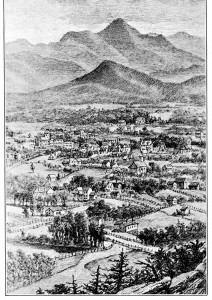

By 1824 the number of drovers crossing through what was then all Buncombe County, (from the South Carolina line to the Tennessee line), had increased so much that the North Carolina Legislature incorporated the Buncombe County Turnpike. George Swain, James Patton and Samuel Chunn were directed to receive subscriptions “for the purpose of laying out a turnpike from Salude (Saluda ) Gap (where old US 25 crosses into SC), in the County of Buncombe, by way of Smith’s, Murrayville (Fletcher), Asheville, Warm Springs (Hot Springs) to the Tennessee line.” The road was completed in 1827. The number of drover’s increased to a flood of drovers after the road was completed. It was said to be the best road in NC at that time. A bridge was built across the French Broad River at Warm Springs (Hot Springs) in 1832. It was rebuilt in 1842 and was 420 feet long. The Buncombe turnpike went from Saluda Gap through Flat Rock, Hendersonville, Murrayville (Fletcher), Arden to the Old Biltmore School just south of Interstate 40. From there the turnpike went a little to the northwest and crossed the Swannanoa River, up Biltmore Avenue, by St Joseph’s Hospital to the Public Square (now called Pack Square). It then went down present Broadway to the French Broad River. The road followed the river past Beaverdam Creek, Reems Creek, Flat Creek, Ivy Creek, Laurel Creek to Paint Rock on the Tennessee Line. The mountainous land between Asheville and Tennessee was the worst part of driving animals from Tennessee and Kentucky.

The French Broad River was the route of least resistance from Asheville to Tennessee. The French Broad River flowed through a gorge. If you followed the river you didn’t have to go over any mountains or steep hills. This not only made for easier travel, but your livestock would lose less weight. Climbing steep hills or mountains would cause your animals to burn more calories and thus loose weight. The fatter your animal the more it sold for. The drovers would follow the riverbanks. In some places the riverbanks were widened to avoid a bottleneck that would slow the herds down. Occasionally they would have to cross to the other side of the river because of a steep bank or cliff. Often an enterprising person would build a ferry at these locations where the drovers had to cross the river. Tolls would run 15 cents for a man on a horse, Five cents for a person walking, two cents for each hog, one cent a head for cattle and ten cents for a horse being lead. Five hundred hogs would cost you ten dollars. That doesn’t sound like much but in those days ten dollars would buy you an acre of land. Drovers could only travel an average of eight miles a day. If they went in faster their animals would loose weight and more of them would be able to slip away into the woods. Stalls or inns were built every eight miles along the route. Drovers would spend the night at these stalls. They would buy corn at around seventy or eighty cents a bushel to feed their livestock. It took around eight bushels of corn for every 100 hogs. The animals were driven in to holding pens for the night and that was when they were fed.

The French Broad River was the route of least resistance from Asheville to Tennessee. The French Broad River flowed through a gorge. If you followed the river you didn’t have to go over any mountains or steep hills. This not only made for easier travel, but your livestock would lose less weight. Climbing steep hills or mountains would cause your animals to burn more calories and thus loose weight. The fatter your animal the more it sold for. The drovers would follow the riverbanks. In some places the riverbanks were widened to avoid a bottleneck that would slow the herds down. Occasionally they would have to cross to the other side of the river because of a steep bank or cliff. Often an enterprising person would build a ferry at these locations where the drovers had to cross the river. Tolls would run 15 cents for a man on a horse, Five cents for a person walking, two cents for each hog, one cent a head for cattle and ten cents for a horse being lead. Five hundred hogs would cost you ten dollars. That doesn’t sound like much but in those days ten dollars would buy you an acre of land. Drovers could only travel an average of eight miles a day. If they went in faster their animals would loose weight and more of them would be able to slip away into the woods. Stalls or inns were built every eight miles along the route. Drovers would spend the night at these stalls. They would buy corn at around seventy or eighty cents a bushel to feed their livestock. It took around eight bushels of corn for every 100 hogs. The animals were driven in to holding pens for the night and that was when they were fed.

The animals were only fed once a day in the evening. They were said not to travel well on a full stomach. Lots of occasions two or three drovers would stop at the same stall for the night. The animals were fed in order of arrival. Almost all of the stalls or inns would have a tavern or at least sell whiskey.

Part two in next month’s Town Crier.

Local historian Bruce Whitaker documents genealogy in the Fairview area.